Having coached swimming professionally for over a decade and worked with swimmers at the highest domestic level in Great Britain. I developed programs focused on creating well-rounded swimmers. I was often limited on contact time with my athletes compared to other clubs, so I had to make the most of the time I had.

There were four main areas I focused on when developing my programs: technique, fitness, strength, and mobility. More recently, I’ve had to double down on the efficiency of my coaching as I now primarily work with adults who have limited time and want to swim faster front crawl. These are things that anyone can do to become a better swimmer. I know that if you can incorporate some of the following into your routine, you will improve your speed.

Improve Your Technique

All sports have principles of efficiency when it comes to technique, but with swimming being a water sport, it makes a bigger difference. Think about it, water is thick! Air has a density of 1.2g per liter compared to water’s 1kg per liter, meaning water is over 800 times denser than air. When you’re putting in full effort but moving slowly, efficiency becomes crucial.

At my local pool, there’s a fast, medium, and slow lane. I often see people in the fast lane swimming at a pace of around 2:30 per 100m, whereas I typically average around 1:20 per 100m. That’s a huge difference, even though we’re both classed as fast. Although I consistently swim 2-3 times per week, one of the biggest factors in our speed difference is technique.

In an ideal world, you would have perfect technique, allowing you to propel yourself forward the maximum distance with every stroke and minimal effort.

Your head should be positioned so that your hips and legs are high in the water, keeping your body horizontal. It should also be still enough to break the water smoothly, creating a lovely bow wave.

You should have a strong, consistent kick that helps you balance and propel yourself forward. The top of your kick should have your heels breaking the surface, with your knees slightly turned in so the top of your foot is flat on the water as you start to kick down. The bottom of your kick should be as deep as your body, with each kick flicking your big toes to keep your legs close together, reducing drag.

Your arms should move in a way that maintains pressure against the water with every movement—either setting up your stroke without causing extra resistance or propelling you directly forward without any wasted side-to-side motion. Your hands and arms should create the largest possible paddle.

You should be able to breathe low and to the side, keeping your body aligned and horizontal without breaking your stroke’s timing or the efficiency of your propulsive movements.

The timing of your arms and legs should help you maintain forward momentum at all times, as well as balance your body position and propulsive movements.

The distance and speed you aim to swim will determine which technique aspects are most important. From both personal and coaching experience, a strong kick offers the most significant benefit for pool events. The smooth, controlled environment of a pool suits longer strokes and stronger kicks, with the turns providing brief rest for your legs. However, for longer pool events, the oxygen demands of kicking outweigh the benefits, shifting the focus to a stronger, faster pull and good body position. In open water, longer events with fewer breaks (as there are no walls to push off from) require a highly efficient body position in the water.

Too many swimmers focus excessively on having a perfect catch and pull when they would benefit more from improving their head position and reducing drag. During every swim, it’s best to focus on one or two technical points, either in specific sets or throughout the entire session. From my coaching experience, it’s most effective to concentrate on just one point until it becomes second nature. It’s easy to move on too quickly and miss out on long-term benefits or try to incorporate too many things at once, causing your stroke to fall apart.

What Sort of Fitness is Required?

Swimming requires well-rounded fitness: cardiovascular fitness, muscular endurance, muscular strength, and good mobility (which we’ll discuss later). Your body must efficiently use oxygen, as you can’t breathe whenever you want, so training your body to use what you do breathe in effectively is crucial. From personal experience, I recommend only taking in a normal breath; inhaling too deeply can cause tension and wear you out faster.

Unless you’re swimming a 50m sprint, you need a solid aerobic base. Having different “gears” to switch through is always beneficial. From experience, swimmers with multiple gears always perform better on race day. I often see swimmers training by swimming up and down continuously for an entire session. Not only would I find that tedious, but it also only builds one aspect of fitness and doesn’t help you develop your gears.

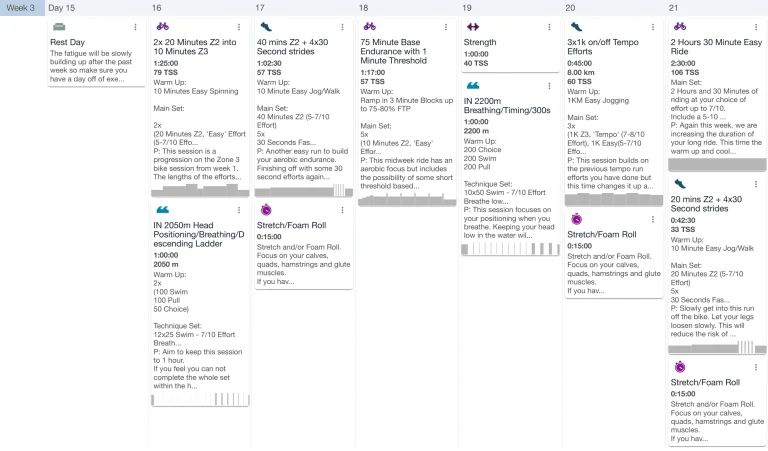

Add structure to your swim sessions, incorporating varying intensities, distances, and rest periods for maximum effect.

Check out this swim session which adds a technique set to a tough session.

If you would like to know the best way to create a swim workout that improves your technique and fitness, check out our handy guide: How to Build A Swim Workout

What Strength Work Is Optimal?

As mentioned earlier, you need good muscular strength to swim fast. If you watched any of the swimming at the Olympics, you’ll see that all the athletes across all distances are incredibly strong! Many of them would put your local bodybuilders to shame in the gym. For example, Adam Peaty mentioned in an interview that he squats 160kg and can bench press 135kg. These are huge numbers for any normal person!

Of course, we’re not all elite athletes, and I know many of you are long-distance swimmers or multisport athletes who understand that too much bulk can negatively affect overall performance. The most important muscles for swimming front crawl, in terms of efficiency and power production, are your lats, triceps, and core. To improve pool speed, your glutes, quads, and hamstrings are also crucial.

Your lats contribute to the power you generate at the front of your pull, the triceps at the back, and your core provides a stable base to push off from—like trying to jump high off solid ground versus a crash mat. You might produce the same amount of power, but the stability of your base affects how far you go. A strong, stable core also improves balance and stability between your arm and leg movements when swimming fast.

Stronger legs help maintain a consistently high pace during sprint swimming by increasing the power of your kicks.

I regularly strength train at the gym with a friend who doesn’t swim and is more of a gym enthusiast. He’s a powerful 105kg compared to my 80kg. In exercises that focus on muscle groups not critical for swimming, like chest presses and bicep curls, he outperforms me comfortably. However, I can do lat pulldowns and tricep extensions at weights that many hardcore gym-goers struggle with, thanks to my swimming background, which really helps in the pool!

Adding gym work will increase your power production in the water at all speeds, benefiting everyone.

What about Mobility?

In my experience, 90% of the best swimmers I’ve coached have been very flexible, either overhead, in the knees and ankles, or all over. Your mobility directly impacts your technique and efficiency in the water, as well as your injury resilience.

Good shoulder mobility reduces the risk of shoulder injuries (like rotator cuff issues) and helps you get your hand and arm into a position where you can apply backward pressure earlier, moving you further forward with each stroke. Think of it as moving yourself past a point in the water—the further that point is ahead of you, the further you’ll travel with each pull.

Good knee and ankle mobility allows you to position your feet to apply force backward, propelling you forward. I’ve coached many cyclists and runners with rock-solid ankles that barely move when their arms are taken out of the equation. This lack of ankle mobility is the culprit, even though they have very strong, fit legs! If you struggle to move with a kickboard, consider adding ankle mobility work to your routine.

Focusing on core and back mobility is also essential. This enables effective body rotation for maximum extension, keeps your body straight and flat in the water (reducing resistance), and helps you control your rotation when breathing, maintaining balance throughout your stroke.

Incorporate mobility work before every strength and swim session, and also after your swim sessions. This can include stretching, range of movement exercises, or yoga-based activities.

What You Can’t Change

There are always things you can’t change. At the elite level, the difference between 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place is usually not due to training regimen differences—you often hear about top swimmers’ training schedules because the media focuses on them. But normally, that’s not what sets someone like Michael Phelps apart from the next best swimmer. It’s often about factors they can’t change. Phelps, for example, is hyper-mobile, giving him a mobility advantage over many of his competitors. Others might have genetic advantages over their opponents too.

This means you can only improve the aspects within your control to the extent your body allows. Focus on consistent improvement in areas where you can, and you will see consistent progress in your ability as well.

If you want to know more on what you can’t change, check out our post on How to Work with your Genetics

We have swim training plans that focus on your technique and fitness, with fully planned sessions that break down your technique into bite-sized chunks. These plans provide structure and consistency without overwhelming you. Check out our swimming improvement training plans.